The Long Reach of Insecure Gig Work in America

By Gregory Lyon

Gig workers provide a range of important goods and services in the United States. Some provide rides. Others deliver groceries or provide cleaning services. Gig workers also provide labor for academic researchers.

These largely unregulated jobs have come under renewed attention recently as the spread of Covid-19 exposes the highly precarious and unregulated nature of gig work, and low-wage work generally. Gig workers lack benefits such as health insurance and paid sick leave time and have no income if they do not provide services -- though the stimulus package currently being negotiated in Congress includes a form of unemployment insurance for gig workers whose work is on hold due to government-mandated social distancing measures. As The New York Times reported “even as public health agencies have recommended social isolation to insulate people from the virus, gig workers must continue interacting with others to pay their bills,” while the Financial Times points to the precarious nature of insecure gig work as a threat to public health concluding “American leaders must start a proper debate about creating a better longer term safety net for gig workers.”

Gig workers are also now beginning to fight back. Instacart’s gig workers are today launching a nationwide strike. A lead organizer of the strike, Vanessa Bain, explained that “While Instacart’s corporate employees are working from home, Instacart’s [gig workers] are working on the frontlines in the capacity of first responders.” Indeed, a series of labor actions are now brewing. Amazon warehouse workers are also planning to go on strike and workers at Whole Foods are now planning a “sick out” for this Tuesday. As Hannah Gold notes in The Cut, “The possibility of a general strike seems more real than it ever has in America as labor conditions have become more dire than they’ve ever been in recent memory.”

The Financial Times reported that the United States is highly vulnerable to an outbreak spreading quickly due to a so-called "triple threat": millions of uninsured and underinsured people, lack of paid sick leave, and an incoherent federal response to the threat.

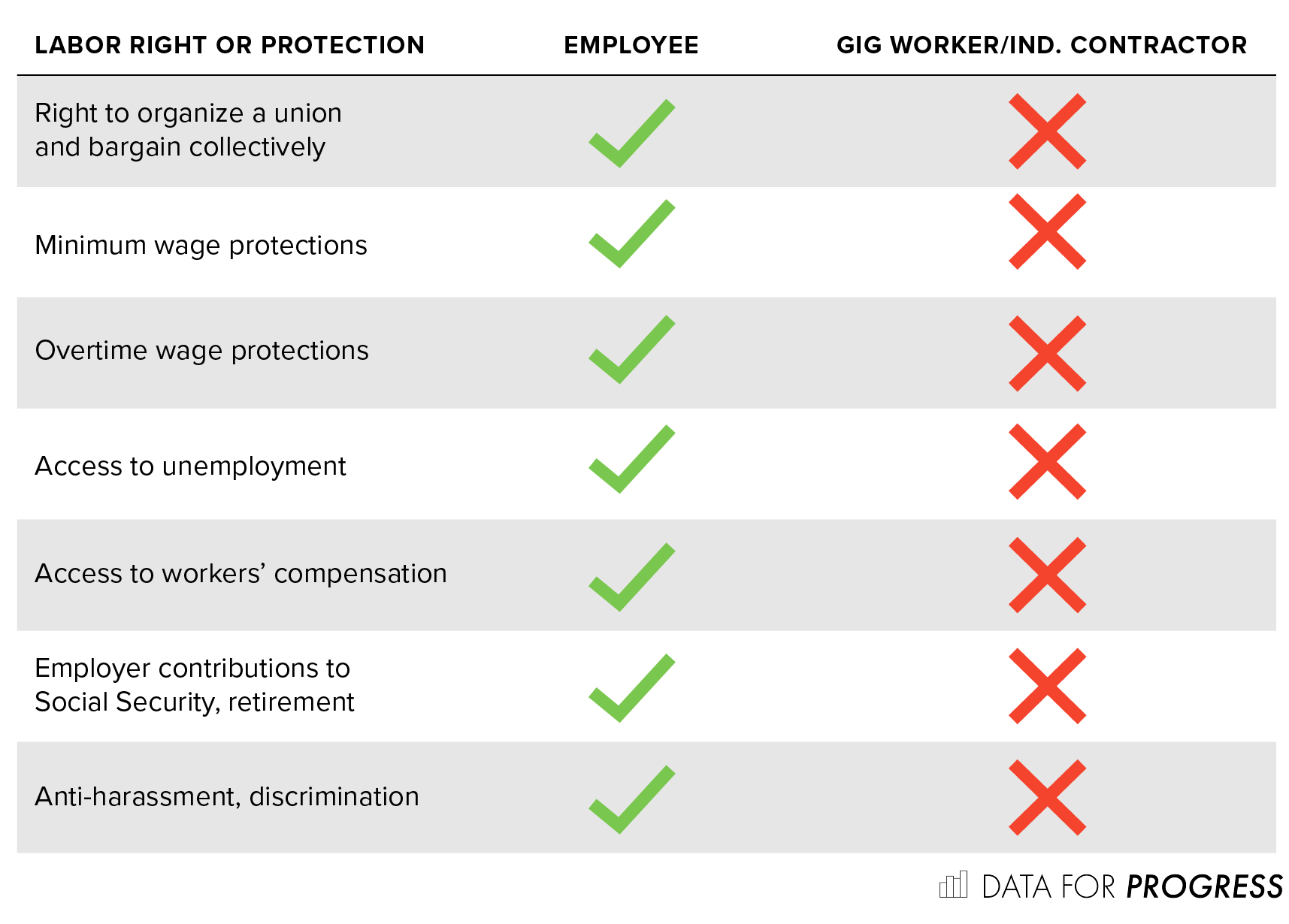

New analysis from Data for Progress reveals how widespread and important the gig economy is, with a quarter of adults drawing income from gig work in the past year. Gig workers, who make up a big part of the first two groups, i.e., those without adequate or any health insurance and no paid sick leave, are largely classified as independent contractors, not employees. What’s the difference? Independent contractors lack many of the basic protections enshrined in federal labor law. Table 1 below compares these two types of workers.

Yet despite the growing interest in an increasingly unequal American workplace and gig work in particular, we know relatively little about the political composition of gig workers. Are they all Democrats? Are they mostly Republicans? This is important. If gig work is an experience shared across party lines, it suggests that policy aimed at helping gig workers may have appeal across party lines.

In order to get a sense of the political composition of gig workers, we conducted a survey in November 2019. Although the survey was conducted a few months ago, aside from the Covid-19 outbreak, there have been few large or systemic changes in the labor market since November so the results we see here would likely hold true even with a more recent survey. The survey asked respondents two key questions: whether, in the last year, they earned money through gig work such as driving someone from one place to another, cleaning someone’s home, or doing online tasks. If they said yes, they were then asked whether the income they earn is “essential,” “important,” or “nice to have.” These questions were modeled off of a Pew survey and sought to gauge the prevalence of gig work as well as the extent to which workers depended on the income it provides. The survey also asked respondents about their political affiliation which allows us to examine gig workers’ political preferences.

The results suggest the gig economy is widespread and growing. In the 2016 survey Pew conducted, 8% indicated that they had earned money from gig work. In our 2019 survey, 24% of respondents said they had performed gig work in the past year, which is largely in line with industry research.

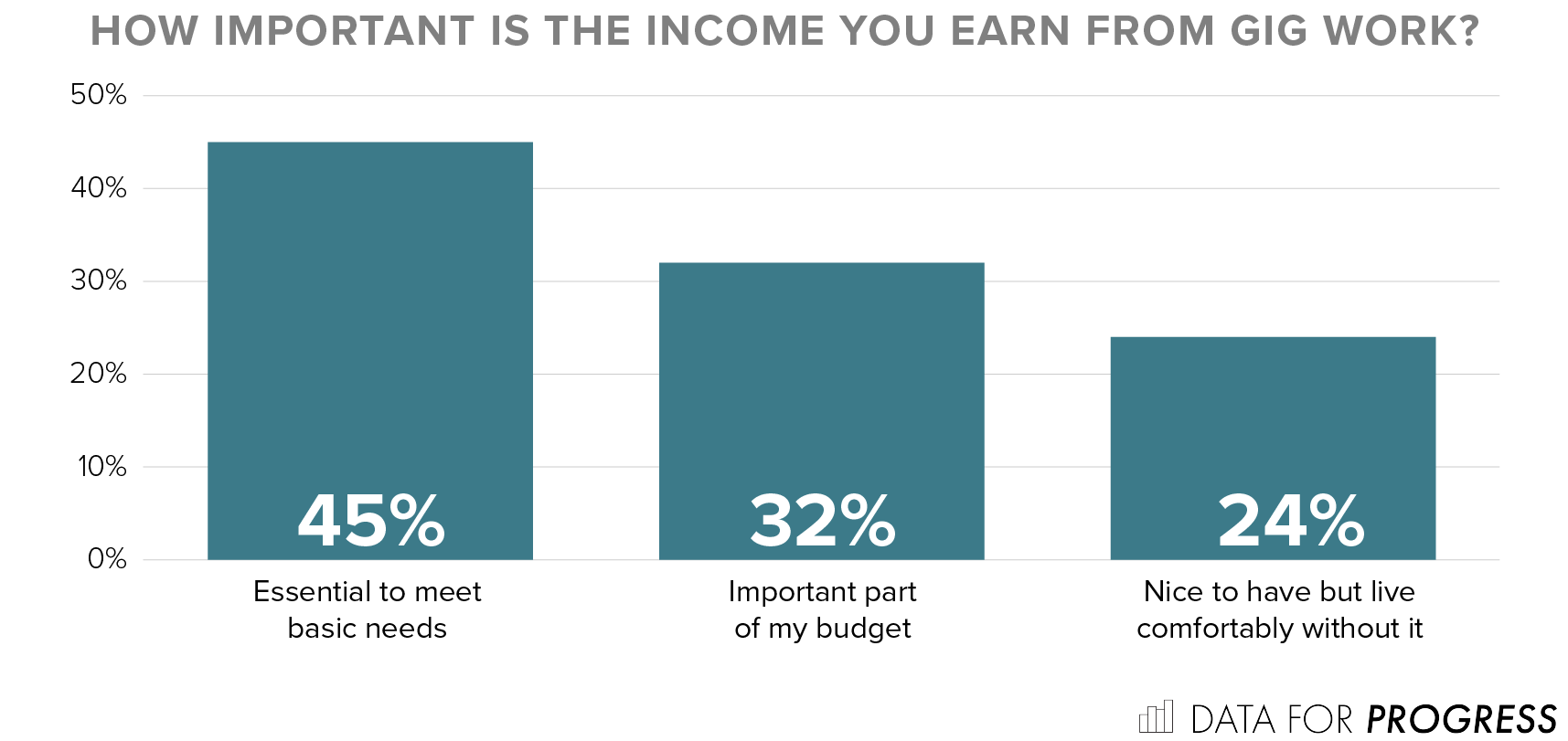

Do gig workers need this income or is it simply nice to have extra spending money? Our results indicate that most workers need the income. Among workers who said they performed gig work in the past year, 77% said that they income they earned was either essential for meeting their basic needs (45%) or an important part of their budget (32%), while only 24% said that the income they make through gig work is “nice to have” but they could “live comfortably without it.”

Gig workers tend to be younger. In terms of age, over 60% of gig workers for whom the income is essential or important are between the ages 18 and 41, as seen in Figure 2. While younger workers make up the majority, 14% of gig workers are 55 years old or older. This is the age at which individuals qualify for senior housing under federal law. More importantly, it is an age group that is particularly vulnerable to Covid-19. The fact that many gig workers are 55 years old or older and out working gig jobs for income that is either essential or important for their basic needs underscores the broad—and potentially growing—reach of gig work in the US workforce and how it exposes vulnerable populations.

Blacks and Hispanics have long been overrepresented in insecure work and among gig workers they are overrepresented as well. In our survey, 21% of gig workers identify as black (while blacks make up 14% of the US population). Similarly, while Hispanics make up about 20% of the US population, 24% of gig workers working for income that is essential or important identify as Hispanic.

Much of policy change depends on partisan conflicts and coalitions. If gig workers are concentrated in one party, appealing across partisan lines in the interest of policy change may be less important. However, if they are not, then policies aimed at helping gig workers may need to galvanize support across party lines. Among those who said they earned income through gig work in the past year, 53% identified as Democrats, 32% as Republicans, and 15% as true Independents (do not “lean” toward one of the parties). As a point of reference, this is fairly close to the distribution of partisanship in the general American public. To see this, we can look at partisanship among respondents in the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). This comparison is shown in Figure 3. Among this general sample of Americans in the CCES, 46% identified as Democrats, 40% as Republicans, and 14% as Independents. This suggests that while gig workers lean slightly Democratic, gig work is an experience shared across party lines.

Men and women engage in gig work at similar rates. Among those for whom gig work is essential or important, 54% are male and 46% are female. However, these numbers mask important partisan differences as seen in Figure 4. Among Democratic gig workers, the gender differences are small: 52% are male and 48% are female, a difference of four percentage points. However, among Republican gig workers, there is a large gender divide. Of Republican gig workers, 62% are male while 38% are female, a difference of 24 percentage points.

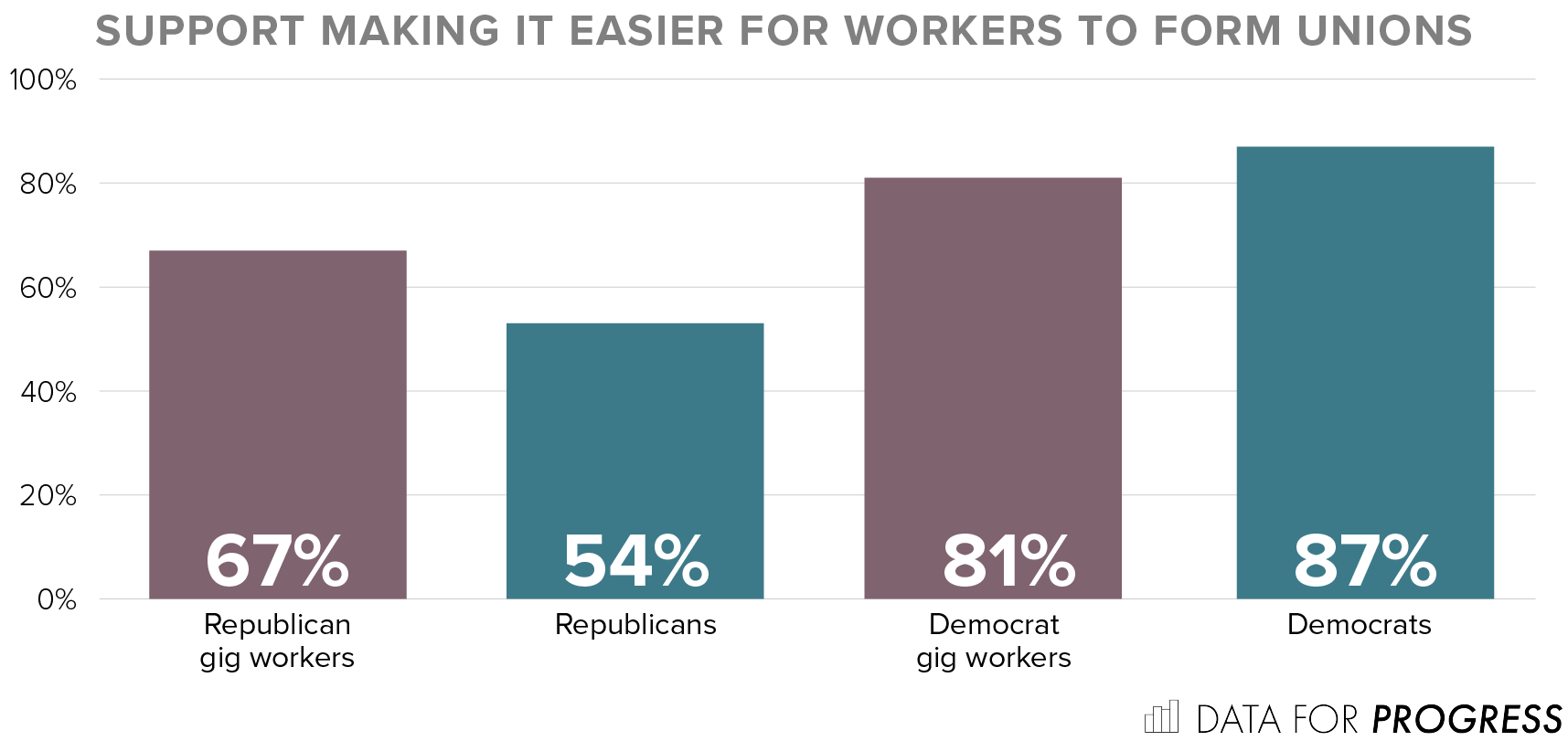

The main way that workers gain better benefits, wages, and working conditions is through forming a union. Unions not only improve benefits but create safer and healthier working conditions, reduce wage inequality, and allow workers to have more control over their work. However, as noted in Table 1, gig workers are not legally considered employees and therefore unionizing is much more difficult as they lack the protections of federal labor law.

In the survey, respondents were asked whether they supported a policy that would make it easier for workers to form unions. Did gig workers differ from their co-partisans? Figure 5 shows the percentages who support this policy by partisanship and gig work status. Democratic gig workers are slightly less supportive than their co-partisans while Republican gig workers are more supportive of such a policy than other Republicans.

Among Republicans, 54% support making it easier for workers to unionize. However, among Republican gig workers who say that the gig work income they earn is either essential or important, 67% percent support making it easier to form unions. Among Democrats, 87% support such a policy, while among Democratic gig workers, 81% support making it easier to unionize.

These results raise interesting questions about how the changing nature of work intersects with American politics. The growth of gig work, a fundamentally political issue, does not appear to discriminate much on the basis of workers' party loyalties. Both Democrats and Republicans are well represented in the gig economy. Moreover, Democratic and Republican gig workers are highly dependent on the income that such work provides them. More than three out of four workers in our survey said that the income they earn from gig work is essential or important for their basic needs.

Although working conditions or workers’ rights can often be seen as partisan issues, the results here suggest that insecure, low-wage, unstable work is an experience shared across party lines. If the Democratic Party prioritized workers' issues and advanced a labor reform bill to bolster workers' rights--especially one that takes aim at gig work, in particular--this may help the party attract support from a sizable share of Republican gig workers who, like Democratic gig workers, toil in insecure, low paying jobs to make ends meet. There is no shortage of ideas--ranging from the PRO Act that recently passed the House (with five Republicans voting in favor) to the comprehensive slate of labor law reforms outlined by a range of scholars and practitioners in the Clean Slate Project.

It will be no easy task. An increasingly wealthy and powerful donor base within the Democratic Party--economic elites from the technology sector--are staunchly opposed to workplace regulation and unions and will vigorously oppose any such efforts. For instance, last year after California passed a bill intended to regulate gig work, three large and powerful technology companies pledged nearly $100 million to defeat and repeal the bill in a 2020 ballot initiative. This suggests the Democratic Party is likely to face decisions about which side they are on—gig workers or gig companies. The persistent erosion of working conditions and fractured nature of work in the US may provide fertile ground to harness the political will to make these policies a reality, but they may find a more receptive audience across party lines than within.

Gregory Lyon is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Tufts University and studies work and politics.